The Millstones

The bedrock has been worked for hundreds of years in Skarvan and Roltdalen National Park. The most important work has been cutting millstones. The history of the millstones has been documented from the 16th century until 1914. The largest concentration of millstone quarries is in Høgfjellet.

The Millstones

The bedrock has been worked for hundreds of years in Skarvan and Roltdalen National Park. The most important work has been cutting millstones. The history of the millstones has been documented from the 16th century until 1914. The largest concentration of millstone quarries is in Høgfjellet.

The millstone quarries

The history of the millstones has been documented from the 16th century until 1914. The largest concentration of millstone quarries is in Høgfjellet. The North-Trøndelag Tourist Association’s marked trails that go between Hoemskjølen and Schulzhytta cross these quarries. The remnants of millstone quarries are today visible in the form of stones, stone quarries, turfs, and tracks. When hiking in the national park, this cultural heritage gives your experience of nature an extra dimension.

Grain has been a vital to the survival of people ever since agriculture came to Norway. Grain was used for both food and brewing beer. To make flour, grain had to be ground; this was done by millstones. These could be small hand grinders or massive millstones driven by hydropower in streams and rivers.

In Selbu, large millstones were mainly quarried for brook mills. The stones could weigh up to 1600 kg. The millstones were made in pairs with a convex stationary base known as the bedstone (or foundation stone) and a concave runner stone that rotates, driven around by a water wheel. In the middle of the runner stone there is a hole – often known as “the eye” – where the grain is poured and then ground between the stones. The milled flour then comes out around the edges of the stones.

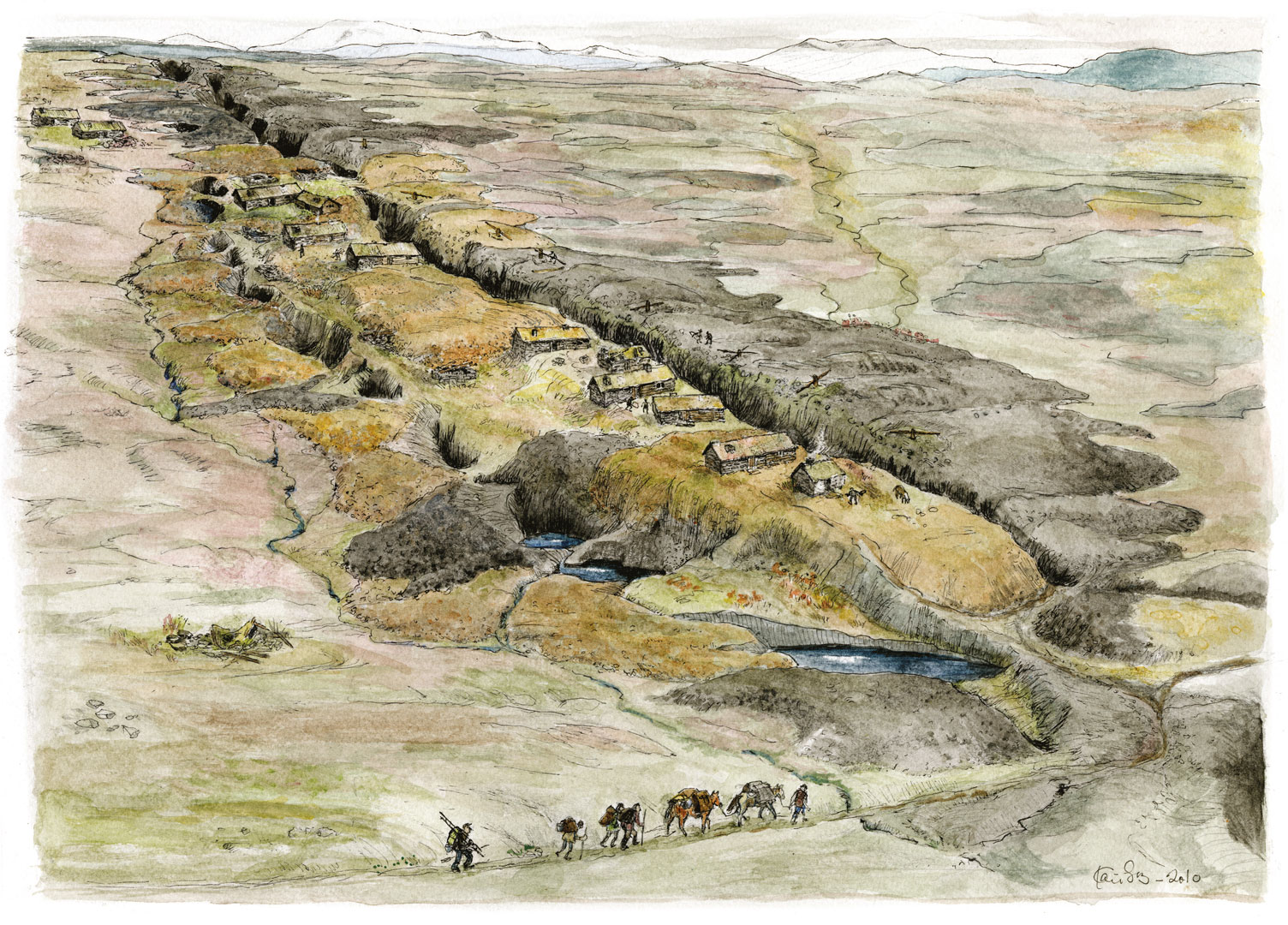

A good millstone is both simultaneously hard and soft. Mica shale with small crystals of garnet and staurolite, evenly spread like small, hard grains that sharpened themselves are optimal. In Selbu, this kind of rock is found running in a long, narrow, fragmented belt – stretching 35 km as the crow flies – from Skarvan in the north, up over Høgfjellet mountain down to Bukkhåmmåren below. The largest concentration of millstone quarries is at Høgfjellet. There are many quarries north and south of Store Kvernfjellvatnet.

Millstones have been produced in several places in Norway, such as: Hyllestad in Sogn, Saltdal, Brønnøy, and Vågå. The production of millstones in Selbu far exceeded the local need, so millstones were exported to other places in Norway and abroad, including Sweden, Denmark, Finland, and Russia. Seblu millstones dominated the Norwegian market, which led to the millstones being important to the local economy.

The area with millstone quarries stretches for more than 30 km from Skarvan in the north to Bukkhammeren in the south. The largest and most significant part of the quarry is to be found in Zone A of the national park, which is one of the most restricted areas. This area is highly protected, and the removal of stones is strictly prohibited.

Work in the millstone quarries

Over the years, the method used to remove millstones changed. In the beginning, millstones were made from loose stones and the oldest quarries were small and shallow. There was no sizeable operation until gunpowder was introduced in the 18th century. After a while, as the quarries became deeper and deeper, they began to fill with water which was a problem. Work in Kvernfjellet started at the beginning of October after the year’s crop had been housed. To begin with, the quarries needed to be drained of water. Without siphons and pumps, this had to be carried out by hand using bailing buckets. It was only in recent decades that siphons and pumps began to be used.

For the first few centuries, work was carried out until Christmas; however, in the 19th century the season was extended to February and then to the end of Easter. The stones were roughly hewn on the mountain side with a sharp iron hammer and chisel. They were then transported by horse and sleigh across the packed ice down to the village. Once in the yard, they were carefully carved and sanded down. Finally, the millstones were sold and transported either by boat from Selbusjøen to Klæbu. From there, they were taken by horse and carriage to the annual Trondheim Martnan Market in June or by horse and sleigh over the mountain to Røros Martnan in February. If they managed to make one pair of millstones during the winter, they were happy.

Illustrations: Karen Støren Binns

The Høgfjell quarries looked approximately like this at the end of the 19th century. The large “mountain cabins” were lined up in a row along the edge of the deep quarry.

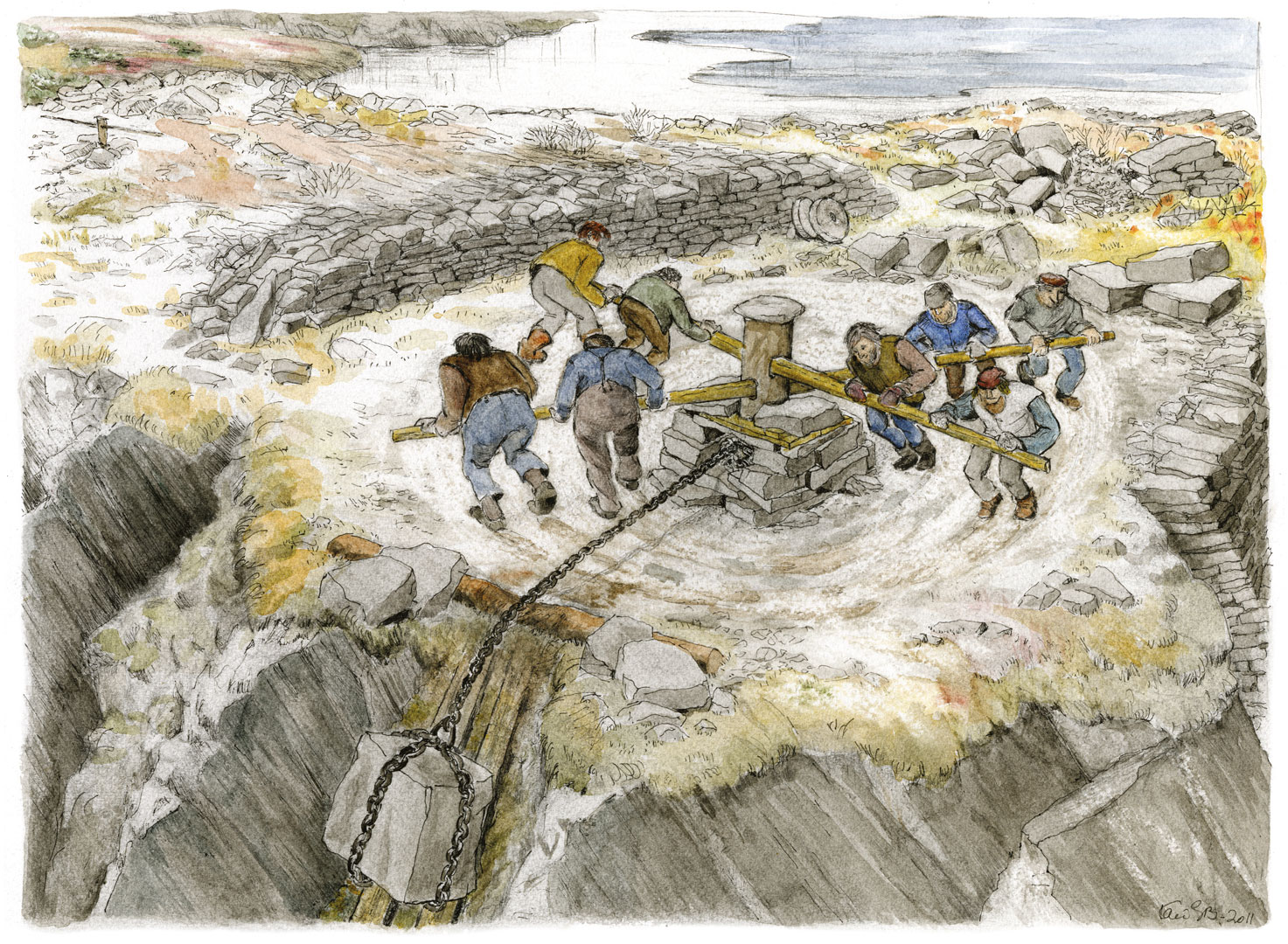

From the end of the 19th century, capstan were used to lift large boulders from the deep quarries.

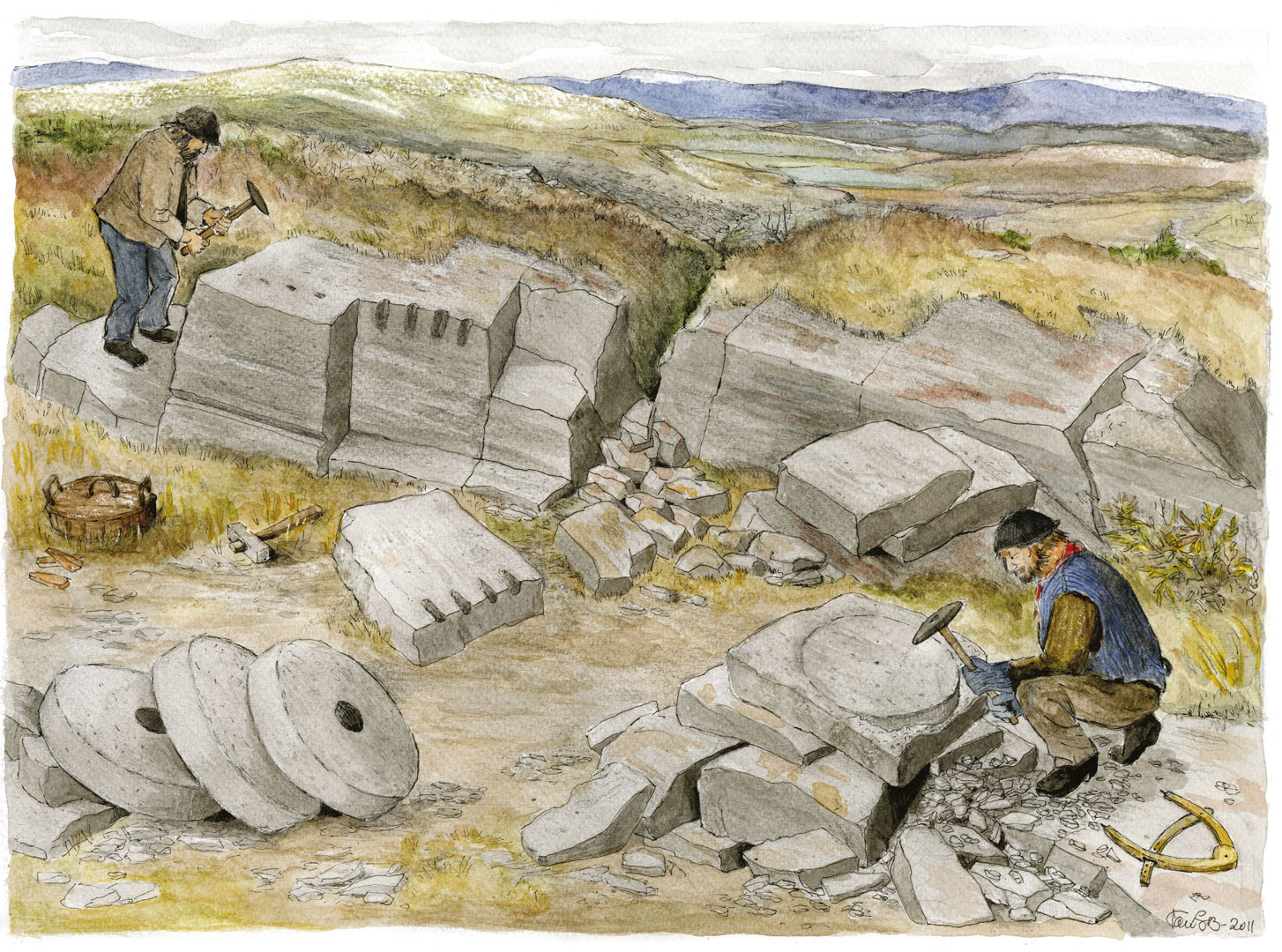

Until the beginning of the 18th century, the slabs of stone were loosened with wedges and picks. The circle was carved out using a compass, and then the stone was cut out using a pick.

Contact us

The National Park for Skarvan and Roltdalen and Sylan

Postbox 2600

7734 STEINKJER

Tel: 73 19 93 11

Email: lars.slettom@statsforvalteren.no